Public-Private Partnership (Transparency and Accountability) Bill

Mr ANDREW: I present a bill for an act to enhance the transparency

and public accountability of the decision-making processes for public-private partnerships. I table the

bill, the explanatory notes and a statement of compatibility with human rights. I nominate the Housing,

Big Build and Manufacturing Committee to consider the bill.

Tabled paper: Public-Private Partnership (Transparency and Accountability) Bill 2024.

Tabled paper: Public-Private Partnership (Transparency and Accountability) Bill 2024, explanatory notes.

Tabled paper: Public-Private Partnership (Transparency and Accountability) Bill 2024, statement of compatibility with human

rights.

The Public-Private Partnership (Transparency and Accountability) Bill provides a framework to

establish a culture of openness and transparency around the state’s commercial deal making with the

private sector. Its primary objectives are: to promote public trust in government; aid in the prevention of

corruption; achieve true value for money for Queenslanders; and ensure that all public-private

arrangements in Queensland are conducted in accordance with the principles of transparency, fairness,

stability, proper management, integrity, accountability and long-term sustainability.

Public-private partnerships, or PPPs, allow private consortiums to finance, build, operate and

deliver public infrastructure and services that have traditionally been the province of government. It is

a model that explicitly relies on the private sector’s profit motive to provide public goods. Here in

Queensland PPPs have been used to deliver nearly everything in Queensland, including roads, tunnels,

railways, energy and water, schools, aged care, hospitals and prisons. Despite all of this, there is still

no specific legislative framework in Queensland to regulate the extensive arrangements between the

public and private sectors. This bill will therefore fill an important gap in the state’s legislation. In doing

so, it seeks to increase public knowledge and trust around how public monies are being spent in

Queensland and what contractual commitments the government is taking on that may bind the state

and its citizens for decades to come. Overall, the bill will make a real difference by providing the people

of Queensland with the tools they need to ensure the state’s massive infrastructure program and

government services are delivered in as transparent and cost-efficient a manner as possible.

In part, the bill responds to various findings and recommendations made by the Queensland

Audit Office over the past decade. On 14 December 2023, the QAO released a report on the state’s

major projects that stated—

Clear and complete reporting on capital projects is critical to building public trust and ensuring accountability.

In relation to Queensland’s PPP arrangements, the Auditor-General recommended that Treasury

update its practices to include details in its summaries on service payments and contributions from private sector companies and to annually publish a report of completed projects in conjunction with the

capital statement showing the total amount of actual expenditure as at completion date.

In Let the sunshine in: review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector,

Professor Coaldrake wrote that the government must be prepared to defend its decision to withhold

information publicly. It stated—

… agencies should not be quick to agree to confidentiality clauses which are proposed by sophisticated commercial parties to

protect their own interests.

As the Auditor-General said in his report on contract management—

… the public has a right to know how much public money government is spending, on what, and with which vendors.

The bill recognises a key principle of democratic government; that is, the public has the right to

know how its money is being spent and whether everything is being done in compliance with all of the

proper guidelines for the allocation of those funds.

On page 13 of the QAO’s major project report for 2023 the Auditor-General provides a

comparative overview of the disclosure requirements for PPPs in Queensland, NSW and Victoria. The

table shows that Queensland’s disclosure requirements are much less transparent than the other two

states. Under Queensland’s guidelines, the government is not required to provide details of a PPP’s

project advisors, risk allocations, contract termination rights, contract modification procedures,

value-for-money analysis, service payments or any of the parties’ contributions, including private

financing details. The guidelines also do not specify any timeframe for the tabling or publishing of a

PPP’s project summary report. As the Auditor-General notes, this can lead to delays, with the

information becoming outdated by the time it actually becomes publicly available.

The bill also introduces a requirement for public sector entities to carry out and make publicly

available its value-for-money assessment on a proposed PPP project. Under clause 13(2)(c) of the bill,

the public sector entity must consider for each step in the project: the priority of the step; alternative

ways of achieving the step; and the costs and benefits of alternative approaches. Clause 13(4) of the

bill requires that a public service comparator also be carried out as part of the VFM due diligence to

ensure that the right model is chosen for delivering public infrastructure and services. The PSC’s data,

methodology and findings must also be made publicly available on a government website.

The bill encourages the public sector to adopt a balanced approach when determining

value-for-money assessments, free of any confirmation bias or third-party influence. All options must

be considered. The reason a public service comparator is so important is because governments are

able to raise capital at a significantly lower cost than private consortiums.

With interest rates continuing to rise, so has the cost of private finance compared to government

borrowings, making PPPs a much more expensive option for delivering the services and infrastructure

the state needs. Governments often use VFM assessments and PSC calculations produced by private

consultants, who almost always find ways to justify using a PPP model instead of public procurement.

This is achieved by using adjustments based on intangible benefits such as ‘efficiency gains’, ‘risk

transfer’ and ‘value-added innovations’.

Proponents of PPPs always like to claim that the much higher costs of PPPs, particularly on the

financing side, are offset by transferring colossal amounts of risk to the private sector. In reality,

however, risk transfer in PPPs is very limited. Risks can never be completely transferred through PPPs

because governments will always be ultimately accountable for delivering public services and

infrastructure. This responsibility is not changed by expensive and highly complex PPP agreements. If

problems arise, it is the public that always has to pick up the bill at the end of the day.

If PPP operators run into problems or do not achieve expected returns, they can just walk away,

leaving the public sector to pick up the tab. Since public services need to continue uninterrupted,

governments have a hard time refusing additional requests by the private partner or charging penalties

for poor performance because the entire PPP may fail. This means the private partner is always in the

stronger bargaining position.

The cost of private finance compared to public borrowing has always been the biggest and

weakest point of a PPP. In 2011, the Financial Times worked out that UK taxpayers were ‘paying well

over £20 billion in extra borrowing costs—the equivalent of more than 40 new hospitals—for the 700

projects that successive governments had acquired under the private finance model’.

PPPs also limit the government’s ability to respond to major economic crises due to their

long-term, inflexible contracts and high costs. When there is a need to cut public spending, for example,it is the services that are not managed by a PPP contract that get slashed. This was confirmed by the

IMF in a 2018 fiscal affairs note, which states—

While spending on traditional public investments can be scaled back if needed, spending on PPPs cannot. PPPs thus make it

harder for governments to absorb fiscal shocks …

It is important to always remember that these PPP consortiums are accountable to their

shareholders, not the people of Queensland. They select projects based on whether they will be

commercially profitable, not on whether they serve the public interest. In other words, they may distort

public policy. The main way a consortium has to profit from a PPP is to cut corners—also known as

‘creating efficiencies’—especially when it comes to staffing levels and the delivery of services. In

Lesotho, Africa, a PPP consortium built a new hospital for which the government had to pay an annual

concession of $32.6 million—almost double the annual budget of the old hospital. Within a year, the

PPP reduced its services, reduced the number of doctors, cut the number of beds and placed limits on

the average length of stay for patients.

To date, the Queensland Audit Office has played a very insignificant role in the governance and

oversight of the government’s PPP arrangements. At the recent estimate hearings, I asked the Acting

Auditor-General whether the QAO had ever performed a performance audit on a public-private

partnership in Queensland. To my astonishment, the answer was no. I have since discovered that only

three states in Australia have ever had a PPP audited by their state auditor-general. They are New

South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia. One study from 2017 stated that over a 22-year period

only 12 per cent of all Australian PPP projects had been audited by a state auditor-general. In

Queensland, it is zero per cent. This means that PPP projects and services in Queensland have been

subject to no independent oversight whatsoever. That is a statistic that I think would shock all

Queenslanders. It certainly shocked me, particularly given the extremely patchy record many of these

PPPs have had in recent times when it comes to cost blowouts, poor service delivery, completion delays

and huge cost increases across the board when the whole thing is up and running.

The national PPP policy has been endorsed by all Australian state and territory governments and

applies to all PPPs that are released to the market. Apart from this, state governments have their own

jurisdictional policies and guidelines around the use of PPPs. However, for the most part, the state’s

Treasury department appears to be the sole agenda setter, rule maker and evaluator of PPPs. Very

little is known about the private sector entities engaged in many of our multibillion dollar PPPs in

Queensland. Many are private investment trusts that have structured their assets and liabilities inside

special purpose vehicles, SPVs, with no obligation to disclose beneficial ownership, financial

statements or majority shareholdings.

PPP transactions have numerous commercial-in-confidence provisions that we are told are

needed to protect the trade secrets of the entities within the consortium. The counterargument to this

is that publicly listed companies are able to disclose their financial dealings to their respective stock

exchange whilst still managing to maintain profitability and the security of commercially sensitive

information. There is no reason, therefore, that these secretive trust companies should not do the same.

Moreover, as most PPP contracts are in areas where there is effectively a monopoly, the argument of

competition should only rarely apply.

With the unprecedented number of capital projects in Queensland’ pipeline over the next few

decades, greater levels of transparency and oversight have never been more urgently needed. The

underlying principle of the bill is that information should be made public unless there is a justifiable

commercial-in-confidence reason for non-disclosure. This means that as much information in a

government PPP contract as possible should be made publicly available, and where this is not done

the government must be called on to justify why not. Under clause 21, the Treasurer must publish

annually a statement containing financial information about each major project undertaken as a PPP

that year. It must also ensure the stream of future PPP payments in government accounts are included

in the annual budget, including which budget these annual costs are being paid from and what the

actual cost to government and the taxpayer will be.

For far too long, unregulated global financial markets have been siphoning away funds from

productive investments in the real economy. As a result, the paper economy has grown but the real

economy has stagnated. Meanwhile, smaller Queensland contractors are being squeezed out of access

to government infrastructure contracts while foreign owned superannuation and private equity trusts

take public moneys out of the state and out of the country.

Democracy thrives when people can see, understand and participate in the decisions that affect

their lives, when decision-makers are accountable for their actions and when leaders lead with integrity. Countless opinion polls show that Queenslanders have lost confidence in their government and elected

representatives. Transparency lies at the heart of all good governance. The more we rely on hidden

and secretive PPPs, the more our democracy is eroded, along with public trust and the infrastructure

and services people actually need—ones based on the public good, not shareholder profits.

It is time to insist on full disclosure, full public consultation, full decision-making and full

accountability from the decision-makers in our government. As the Auditor-General said, there should

be no secrets when it comes to public money and how it is being spent. I am confident that this bill will

deliver a robust legislative framework for the future—one that ensures the affordable and transparent

delivery of the critical infrastructure and services that all Queenslanders need. I commend the bill to the House.

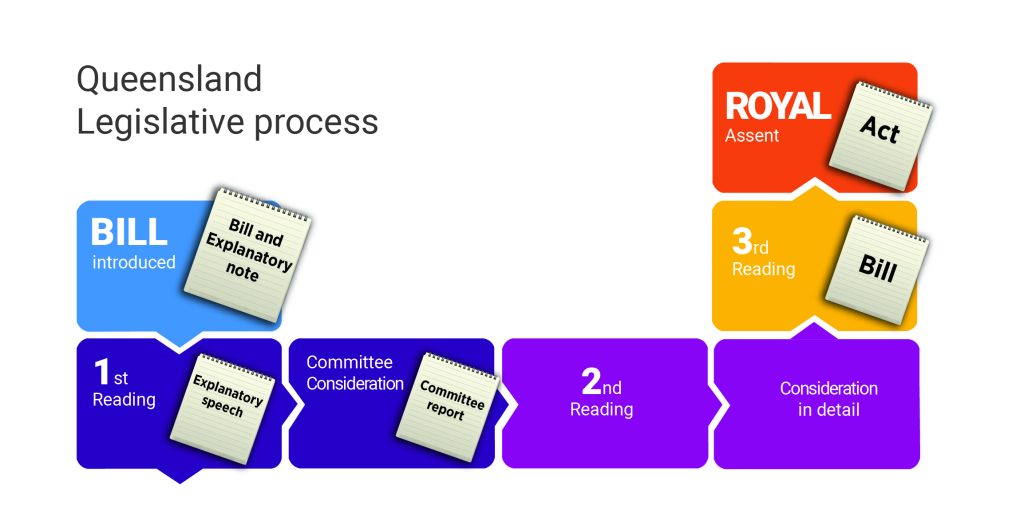

First Reading

Mr ANDREW: I move—

That the bill be now read a first time.

Question put—That the bill be now read a first time.

Motion agreed to.

Bill read a first time.

Referral to Housing, Big Build and Manufacturing Committee

Madam DEPUTY SPEAKER (Ms Bush): In accordance with standing order 131, the bill is now

referred to the Housing, Big Build and Manufacturing Committee

No responses yet